If Boston 2024 succeeds in its bid for the summer games, it will be the first U.S. Olympics in 22 years. That’s the longest gap between either summer or winter games hosted in the U.S. for more more than half a century. In fact, part of the pressure heaped upon the United States Olympic Committee in regards to Boston’s bid is the weight of the current drought. Yet there are very specific reasons why the most recent U.S. bids failed during this period, and it doesn’t necessarily bode well for Boston.

New York City, 2012

New York’s bid encountered serious internal difficulties, centering around the proposed “West Side Stadium” that would’ve been the centerpiece of the 2012 Summer Games as well as its legacy. From the outset, organizers of the bid proposed that public funding would be used to help finance the Manhattan-based stadium, with the eventual legacy being a new residence for the New York Jets. (One major issue with the project was that it required the building of an expensive concrete and steel slab that would’ve allowed the stadium to sit on top of existing rail yards.) The project never received the kind of approval that it required, ultimately dying a protracted death in New York legislature.

From there, the New York bid never fully recovered. Given also that it was going up against tough competition from Madrid, Paris (which will bid for the 2024 Games as well) and London (which ultimately won), New York found itself in an untenable struggle.

According to the New York Times, who recapped the city’s defeat after the IOC chose London’s bid in July, 2005, the British emerged victorious because of their last minute lobbying effectiveness. New York misplaced their hope in a Russian voting block, which transferred its support to Madrid instead of the Americans. It was a race for votes, and New York simply couldn’t find enough.

Other more vague reasons for defeat included poor timing, since the U.S. had only recently hosted the Summer Games in Atlanta ’96. Additionally, U.S. foreign policy was not overly popular in 2005, with the recent invasion of Iraq.

These factors ultimately led to the bid’s defeat. Unlike the possible premature bid downfall in Boston, New York’s proposal survived the early candidature stages, making it all the way to the IOC vote. Once there, however, it died an unceremoniously quick death.

Chicago, 2016

More than the New York bid, Chicago was a shockingly swift defeat for the USOC. Despite support from figures like President Obama, the bid garnered the fewest votes of final bid applicants during the IOC selection process in October, 2009.

Explaining why Chicago was dealt such a stunning loss is less about the internal stability of the bid (as is often the case in discussion Boston 2024), and more about IOC politics.

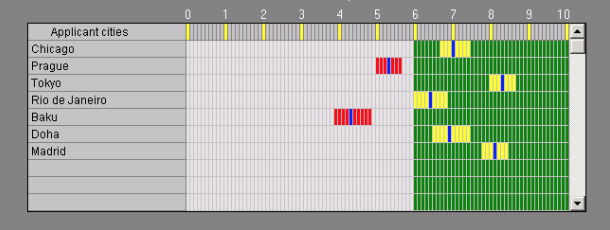

For example, the IOC bid evaluations, determined by a wide range of factors, ultimately placed Chicago as the third most qualified city, well ahead of Brazil’s Rio de Janeiro:

Yet somehow, not only did Chicago lose, but so did other bids (Madrid and Tokyo) who were more qualified than Rio to an even greater extent. The explanation was rooted in a basic premise: Brazil offered a chance to put the first Olympics in South America. Though many question marks remained regarding its bid, Rio emerged victorious.

Conclusion

For Boston 2024, a few notable points remain relevant from the examples of New York and Chicago. Here are some observations:

- Never underestimate the voting strength of a “first” cause. Rio proved that an otherwise underwhelming bid could prevail against traditional European and North American powerhouses, simply because it was the “the first.” As history proves, IOC voters are sometimes swayed by the possibility of the Olympics going to a country or continent where it hasn’t previously been. “The first South American Games” was a persuasive argument. Were an African city to bid (another continent where the Olympics have never been) it could prove to be a difficult opponent.

- Whatever might be said, backroom delegate-wooing is far from dead. The lesson of New York’s failed bid was mostly that IOC voters are still susceptible to last-minute persuading from various bid lobbyists. No matter what official rules might mandate, London 2012 chief Sebastian Coe and then-Prime Minister Tony Blair twisted voter arms right up until it was time to choose. They outmaneuvered the supposed favorites (Paris) as well as the New York bid.

A final point is an ominous one for Boston 2024, considering its need to boost public opinion in regards to funding. IOC voters are not impressed with bids that don’t provide financial guarantees to backstop any cost overruns. Even though Chicago 2016 finally did do so shortly before the voting, the delay was seen as a potential shortfall in the bid evaluation:

At the time of the visit, contrary to IOC requirements, Chicago 2016 had not provided a full guarantee covering any potential economic shortfall of the OCOG which includes refunds to the IOC for advances in payment or other contributions made by the IOC to the OCOG which the IOC may have to reimburse to third parties in the event of any contingency such as full or partial cancellation of the Olympic Games.

While this is certainly not ruinous news for Boston 2024, it again showcases the pronounced difficulties that the current bid faces. Funding concerns are at the heart of the opposition (or even basic skepticism) of Boston’s prevailing attitude. Yet the IOC doesn’t normally suffer a host city being what it perceives as flippant about its financial guarantee.

And even if Boston’s ability to win battles behind closed doors (as they did in securing the USOC’s endorsement in January) is not necessarily a good thing. The bidding environment of the last-minute lobbying can lead to expanded proposals and budgets, and was one fact that helped push London 2012 over its original budget.

Still, examining past U.S. failures produces not all bad news for Boston. The supposed “anti-American” perceptions of the last decade have rescinded (if only slightly), with undeniable improvements having been made in USOC-IOC relations. And the charge that the U.S. “just hosted” falls particularly flat in the bidding for 2024. After all, Boston’s main competition stems from Europe, where two of the last three Summer Games have been held.