Last week the City of Boston approved the FY 2016 budget proposal, which constitutes $2.86 billion, a 4.4 percent increase over the FY 2015 budget. Included in that is an initiative to make free, public-access Wi-Fi more available to the masses – that is, 260 wireless hotspots scattered throughout the city come 2016.

Since its introduction back in 2014, Wicked Free Wi-Fi (as the network is so aptly called) has been met with a tremendously positive show of support and has helped serve under-resourced areas of Boston where wireless connectivity is not easy to come by, whether financially or otherwise.

In that regard, Wicked Free Wi-Fi is a supplemental means for residents and some businesses to forego an otherwise costly wireless service while also helping bolster economic development and digital equity.

Chief Information Officer Jascha Franklin-Hodge said that the 260 hotspot target for 2016 is more of a benchmark and that the success of Wicked Free Wi-Fi isn’t contingent on the number of hotspots deployed. Rather, it’s based on the number of residents served. If the past year’s usage data is any indication, 2015 through 2016 will accomplish exactly that.

If we can say that we deployed one hotspot and made wireless available to 500 or more people, that’s a success.

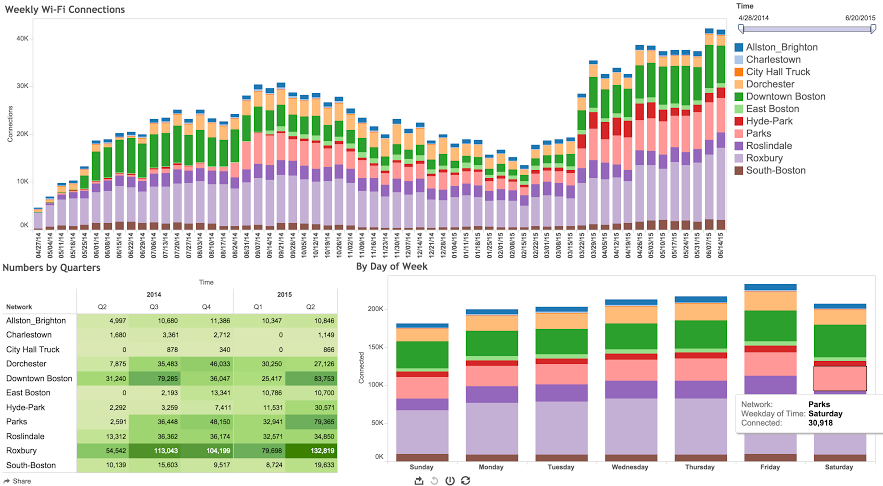

“The program has done great,” he told BostInno. “Looking at our historical usage data on it, basically what’s happening is every week this year so far we’ve more or less set a new record for usage of the network.”

The primary focus for Franklin-Hodge and his team is to bring Wicked Free Wi-Fi to all 20 Main Streets Districts in the City of Boston. Some public spaces – like Boston Common, Moakley Park, parts of Franklin Park and more – boast connectivity to date but increasing Wi-Fi accessible parks citywide isn’t necessarily a priority.

DoIT can, however, kill two birds with one stone by strategically hooking up the Main Streets Districts where outdoor space can also be leveraged.

In Roslindale Square, for example, there’s green space and a public library in close proximity to the several surrounding businesses. Outfitting Roslindale Village Main Street District with Wi-Fi likely will mean Wi-Fi for park goers as well.

Though winter Wi-Fi usage drops considerably (do I really have to remind you what February weather was like?), the city has seen a boom in connections since the beginning of June alone. In just two weeks this month, more than 40,000 people have signed in to Wicked Free Wi-Fi and Franklin-Hodge expects that to continue growing.

The most connections currently come from the areas most densely hooked up such as Roxbury, Downtown Boston, Dorchester and parks.

Supporting that growth, though, is hardly a precise science.

“To be frank, a lot of the decision for where to go is opportunistic,” said Franklin-Hodge. “We found that some locations, for whatever reason, are easier to get to than others. Eventually you need one or more places where the wireless access point is plugged into a fiber optic network.”

So what does that mean exactly?

Franklin-Hodge’s Department of Information & Technology (DoIT) deploy wireless hotspots in places, called backhaul points, that can plug into the network – for example schools, public libraries, police and fire buildings etc.

Surrounding these backhaul points are access points that link to each other and provide wireless coverage over a more extended range.

What’s happening is every week this year so far we’ve more or less set a new record for usage of the network.

Finding viable backhaul points can be difficult when one isn’t particularly close to another and figuring that out is paramount to deployment for the next set of neighborhoods designated to receive Wicked Free Wi-Fi.

But this issue has provided DoIT the opportunity to get creative with its solutions. In East Boston, DoIT is able to tap into streetlights that generate electricity 24/7 to provide a sustainable source of power as well as backhaul density.

The department is also in talks with local businesses to see if the City of Boston can install hotspots on their roofs.

Many are excited to help, Franklin-Hodge noted, and this provides DoIT some dexterity in that it doesn’t necessarily have to install these hotspots strictly on municipal property.

If these businesses are built with certain materials, too, people can connect inside as opposed to strictly outside. It’s no guarantee, however.

“The issue with Wi-Fi is that it’s not a perfect technology,” added Franklin-Hodge. “Even if you have a hotspot in a house you have dead zones where you can’t get online. It’s hard for us to predict or say definitively if a hotspot will be given inside a building.”

But, he said in closing, “If we can say that we deployed one hotspot and made wireless available to 500 or more people, that’s a success.”