Though Boston has historically grown outwards into the ocean, with landfill expanding its boundaries over the decades, the threat of it being submerged back into the Atlantic is very real. Though the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has introduced numerous legislation in an attempt to curtail rising sea levels, as has the City of Boston, there needs to be a shift in thinking from how we can combat the effects of climate change to how we can adapt to them.

Back in August the City of Boston, Boston Redevelopment Authority and The Boston Harbor Association teamed up to solicit ideas from designers, environmentalists and humanitarians in the form of a competition for how Boston can implement urban design changes to adapt with rising sea levels.

And while it’s great to garner public opinion on imminent changes poised to affect every single one of us, the timeline for such an undertaking isn’t working in our favor.

A new report published by the Urban Land Institute’s Boston/NewEngland branch makes a number of municipal design suggestions and reaffirms on several occasions that the time to act is now.

The study, called The Implications of Living With Water, examines four specified areas dangerously at-risk should Mother Nature decide to unleash her wrath in the form of a hurricane not unlike Sandy, which devastated the Eastern seaboard from New York City down to Florida.

Revere Beach, the Alewife Quadrangle, Back Bay and Innovation District were the sites chosen to exemplify how a new way of building could not only alleviate the concerns and subsequent havoc as a consequence of climate change and rising sea levels; it also could designate Greater Boston as the example for swift and skillful planning and construction by which many other metropolitan regions around the world could look to.

To help pique your imagination and give you a sense of what ULI is going for, here are seven designs that predict how Boston could deal with rising sea levels:

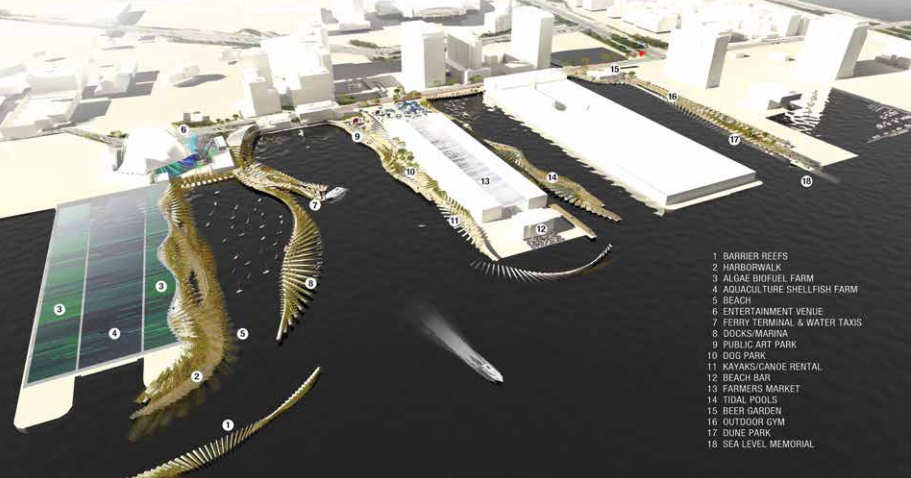

1. Reimagining the Boston HarborWalk

The HarborWalk is basically the only thing standing between Boston Harbor and the Innovation District. So why not use it for dual purposes – aesthetics and fortification? By creating a synthetic reef to act as a barrier for flooding and riddling the HarborWalk itself with pieces of green and porous material to absorb excess water, the Innovation District coastline could be salvaged.

And if such a plan were implemented, it would have to be done so that the HarborWalk could accommodate the ebbs and flows of the tide. This could open the door for additional recreational and development opportunities along the waterfront.

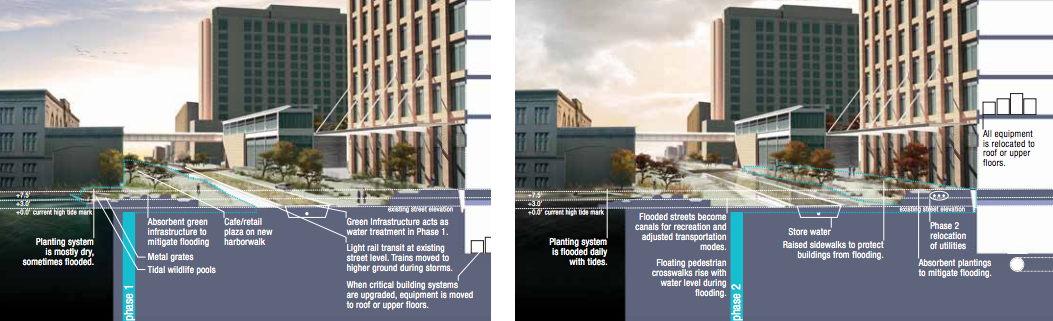

2. Building-to-building infrastructure and raised sidewalks

The Innovation District actually has the benefit of being underdeveloped, as buildings continue to proliferate before our very eyes. But what good are they if access to them is under water? The below rendering shows that access from one building to another, in what’s increasingly becoming an area dense with high rises, could be achieved through connective walkways.

Raising sidewalks is also an option as it would allow for pedestrian access during times of excess flooding as well as storage directly beneath the pavement. Storage could be used to store water or other necessary utilities. In order to implement this, the study suggests bolster public-private partnerships “into which all developers/owners would pay to finance infrastructure-scale resiliency measures, such as a seawall/harborwalk, canals, or green infrastructure.”

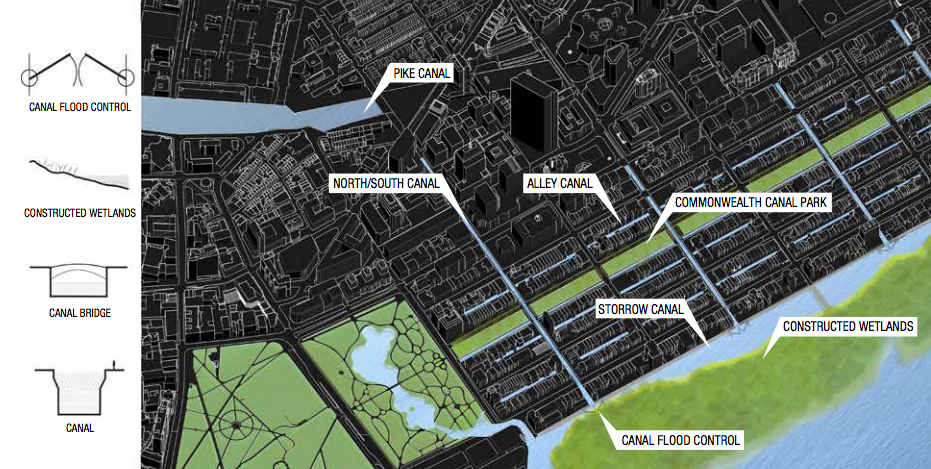

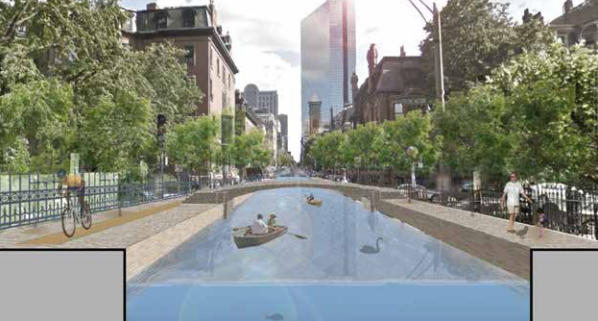

3. Emulating Amsterdam and Venice by building canals in Back Bay

Can you imagine trekking down Commonwealth Avenue in a gondola? While that might not be the preferred form of aquatic transportation, canals in Back Back could save it from literally going under. “To accomplish this,” the report notes, “alternating north-south streets and east-west alleys will become canals.”

What’s great about this idea is that it not only creates a method for flood retention, absorption and distribution, it also opens up the possibility for new modes of transit, increased aesthetics and a reason to “celebrate living with water much in the way Venice and Amsterdam have for centuries.” If, over time, the Charles River Dam is no longer able to police the water levels of the Charles River Basin, “a more decentralized flood control system will be provided through canal inlets located along the Storrow Canal.”

4. More seasonal pop-up retail

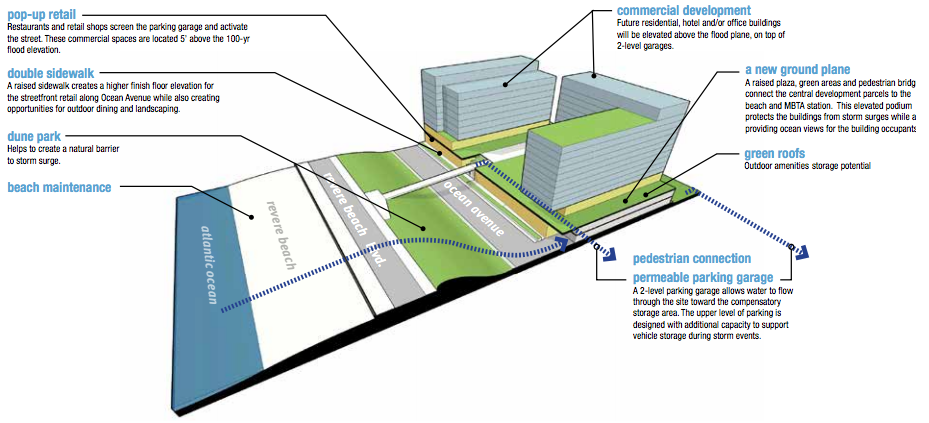

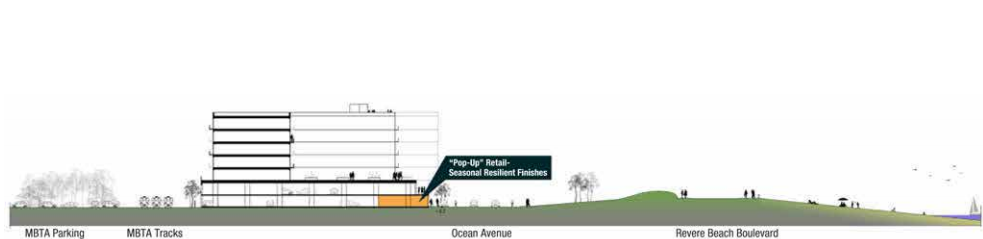

Pop-up shops are already a strategy for retailers to keep their brand and offerings fresh for the public. This idea, though, could be used by at-risk storefronts that maintain a permanent address near hazardous areas. Development along Revere Beach, for example, is actually below the sea level making it particularly susceptible to hurricane and flood damage.

One solution to this would be to open these stores on a seasonal, pop-up basis. Though this would definitely affect revenue for these individual small businesses, one of the big takeaways from the report is that inaction is more expensive than action. And by possibly including them on a higher-level than the ground floor, implementing building-to-building infrastructure is also a possibility here.

5. Dextrous parking garages

Street parking and underground garages, in close proximity to Revere Beach, specifically, makes vehicles prone to climate change damages. Though continuous building up may not be the answer, building smarter garages could be. If parking garages were constructed with the ability to handle excess auto loads, vehicles could be moved from one floor to another in times of turmoil.

But as is the case with a number of the other initiatives, this is contingent on positive collaboration between the City of Revere, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and developers. Instituting tax breaks for environmental projects like this, suggests the report, are likely to incentivize and expedite the process.

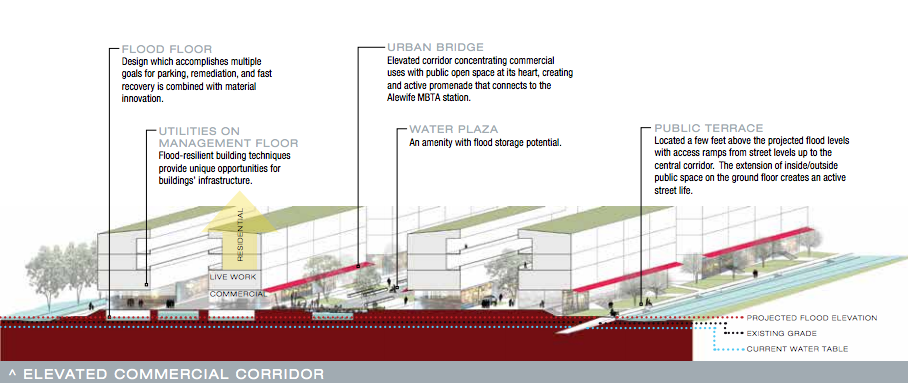

6. Elevate areas around commercial corridors

The Alewife Quadrangle is situated within the Mystic River watershed and therefore, equally vulnerable to flooding as those with more coastal situations. “A coastal storm surge that breaches or flanks the Amelia Earhart Dam on the Mystic River would likely cause Alewife Brook to back up,” notes the report. “As sea level rises, the probabilities will shift upward.”

We’ve already seen ideas for raised pathways, sidewalks, garages and storefronts, but for an area like the Alewife Quadrangle, entire elevated commercial corridors may be the solution.

“Because it is difficult for brick-and-mortar retail establishments, such as restaurants or stores, to allow periodic flooding, a remaining strategy that maintains active street life could involve elevating the area above the flood level,” the report suggests further. “Since for practical reasons the entire Quadrangle cannot be entirely filled, this strategy involves creating a central raised corridor for retail uses.”

Michelle Landers, director at ULI Boston/New England told me in an email that some of the ideas put forth in the study are more realistic than others. But that doesn’t mean we should hold back on generating ideas and solutions to make Boston an everlasting city.

In order for some of the more immediate and crucial projects to get underway the need for legislative funding, fruitful partnerships between public and private entities and detailed climate action plans are just as high of priorities as construction.