In city government, coming up short and failing to deliver is not a comfortable notion to accept. But for innovation to blossom, it’s crucial for success. Boston is a testament to that thanks in large part to a civic innovation lab nestled in City Hall that’s empowered to experiment – and fail – called the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics. They are the motor that keeps this municipal machine thinking forward.

When it comes to technology, some Bostonians may recall that Mayor Walsh’s predecessor, the longest serving mayor in the city’s history, Tom Menino, refused to house a computer on his desk and only adopted a Twitter handle in the twilight of his longstanding career at the helm of The Hub.

If they don’t have any failures, they’re not trying hard enough.

But many of the initiatives witnessed during the first year of Mayor Walsh’s tenure were built upon the foundation laid by Mayor Menino. The ever-expanding Innovation District is one of the larger-scale aspects of his enduring legacy, another being the New Urban Mechanics.

Founded in Boston in 2010, the New Urban Mechanics was such a popular idea that the City of Philadelphia created its own two years later. Though it might go against one’s natural instinct, their job is essentially to fail over and over again, until they come up with a viable solution to a public need – potholes, say, or parking – that not only works, but is easily adoptable by the masses.

Working unconventionally is paramount to their success. And other cities besides Philadelphia want to duplicate this. New Urban Mechanics Co-Founder Nigel Jacob isn’t quick to name names just yet; but he gets calls about it a lot. On the surface, the reason seems clear: Here, you have a City-sanctioned innovation lab that’s expected to come up short until it lands on something innovative and enactable.

“Our job is to be the experimentalists,” Jacob said. “We’re constantly iterating and tweaking as we go.”

The thing about NUM is that the mechanics don’t work on any specific experiment or by any strict agenda.

To get a sense of what their work does entail, consider just some of the facets that make Boston tick: a top-notch educational system, constant street-level infrastructure improvements, public art displays, and tech-focused traffic and parking startups, to name just a few – NUM looks at how all of these can be improved, even if the need isn’t immediate, in hopes of benefiting everyone.

That’s how Citizens Connect was born. This free mobile app is arguably the most successful experiment devised by NUM, allowing ordinary Bostonians to alert the city of street-level issues such as graffiti, potholes or broken infrastructure.

Closed Damaged Sign report at 135-141 A St http://t.co/p7zPZiVdHp. Case closed. case resolved. work completed 12/11/14.

— CitizensConnect (@citizensconnect) December 11, 2014

The alerts are sent to the Public Works Department, recorded online in real-time, and taken care of by personnel at the earliest possible convenience. Taking into account that not everybody carries a smartphone with them, NUM allows people to text, email or call the city and the same ticketing process is commenced. This act of “data donorship,” as it’s referred to by NUM, is a common theme.

But Citizens Connect wasn’t created overnight. The New Urban Mechanics went through at least three versions of the program before it was made widely available. They added features like social sharing, a map pinpointing the issue, and a notice to the person who submitted the issue upon solving the problem.

Not every experiment, though, is contingent on expanding the mutual relationship between the city and the public. Some, like Bird’s-Eye Boston, are public art projects that add character to an underutilized space. Others, like the newly installed #WickedCoolTree – a computer-rigged holiday tree in City Hall that lights up when anyone tweets a color and the hashtag – make desolate, cavernous spaces like City Hall plaza more inviting for Bostonians and tourists.

Really, the constraints in which NUM work are bound only by the imagination of the mechanics themselves, the Mayor’s Office and the public. Without the license to fail, and they fail a lot, they could not succeed.

“I want Boston to be a thriving, healthy, innovative city, and the New Urban Mechanics is one key way we are delivering on that vision,” Mayor Walsh told BostInno. “They’re testing new ideas and supporting all of our City departments in exploring new and better ways to serve our residents, visitors, and businesses.”

The Team

The NUM roster is six people strong, all of whom bring a wealth of expertise and enthusiasm to their roles as well as – perhaps more importantly – an ability and willingness to experiment outside their realm of expertise.

The office is located behind closed doors, in close proximity to Mayor Walsh’s as well as that of his chief of policy, Joyce Linehan. The setup breeds teamwork. There are no cubicles, just open desks surrounded by dry erase boarded walls littered with scribblings of new endeavors, prospective ideas and investigations into what has and hasn’t gone according to plan.

The team is helmed by NUM co-chairs Jacob and Chris Osgood. Jacob, who made his bones in IT and worked in the previous administration as a senior technological advisor, and Osgood, a Harvard MBA who worked as chief of staff to the New York City Parks & Recreation Department before also signing on as a Menino advisor, are a Stockton-and-Malone-type of tandem instinctively feeding off each other’s ingenuity.

In alley-oop fashion they set themselves up to forge and manage key relationships with constituent city departments, as well as lend a guiding hand to whatever their team is working on. When Mayor Menino crafted the idea for a revolutionary new tech department, he turned to his two former Urban Mechanics Fellows, Jacob and Osgood.

“We spend a lot of time with departments, relationship building, building trust and delivering on whatever’s asked of us. A lot of our work is focused specifically around education, or engagement or streetscape, economic development, stuff like that. That real work is led by these four,” added Jacob, introducing his colleagues.

Kris Carter takes up many of the transportation and streetscape lab efforts, which consist of anything from parking prices to vehicular side guards to protect bikers and pedestrians from potentially harmful trucks. Perhaps most notably, though, he helped navigate NUM through the ill-fated Haystack debacle when the Baltimore-based company tried to take a we’re-here-get-used-to-it approach to launching in Boston, ŕ la Uber; insisting they were selling information rather than profiteering off public property eventually led to them being squashed by City Hall.

Karter says they’re meeting with startups, many, like newly launched SPOT of the parking variety, on a daily basis now, hosting multiple sit-downs throughout the day.

“Since Haystack, everyone feels they should come in and talk with us which is great. We love hearing about [their ideas and] we love seeing that there’s a lot of interest in the marketplace,” said Karter. “If you’re an app developer it’s a pretty good time. The single greatest thing in the world for transportation right now is the smartphone. It’s providing all these mobility options that didn’t exist three years ago.”

Michael Evans pitches in on streetscape items as well as heads up digital art installations and engagement competitions. He worked on the Public Space Invitational, which yielded not just artworks such as Liz LaManche’s Stairs of Fabulousness, but also tech such as an outdoor life-size video conference between Boston and other cities to be determined, the musical Tidraphone along Fort Point Channel and a reimagining of street-level furniture.

His latest task was determining a winner for the “Fenway’s 30 Second Cinema” competition. Twelve winners were chosen to display short digital art works on a sign overlooking the corner of Ipswich and Landsdowne streets.

Each video runs for 30 seconds in rotation starting at the top of the hour. The winning artists all banked $300 for their victories.

Patricia Boyle McKenna has worked extensively on sustainability projects, education and municipal operations. She credits Project Oscar as her pet project – two compost bins located in North End and East Boston – to help snowball a massive environmental effort to reduce the city’s carbon footprint.

But Boyle McKenna is also working on what Mayor Walsh has come to call Boston’s “Digital District.” The essence of this (not a district in the sense of a quartered-off space) is to provide teachers, students and parents the tools necessary to perform at an optimal level in an increasingly tech-centric world. And it extends beyond grade school into higher-education: NUM has partnered with Harvard, Boston University and UMass Boston, to name a few, on projects dedicated to innovation education and public policy.

“We thought about how to infuse technology into the curriculum and how we can help engage parents in a different way we’ve never done before,” said Boyle McKenna. “[For example] low-tech, high-tech, supporting teachers, supporting schools with the likes of technologists-in-residents.”

Susan Nguyen is a one-year fellow at NUM and has a hand included in just about everything. Her project focus has been to to make City Hall, and Boston’s neighborhoods more accessible. The idea of sourcing local coffee shops for a cart to be set up in the City Hall lobby and public art project Block Quotes is to make City Hall and Boston neighborhoods more accepting and pleasant.

Already people are taking lunch and meetings at the City Hall mezzanine and Block Quote was a hit at the Boston Book Festival.

“We’re making the city and making this actual building more accessible to the public, and in that way making governance more accessible to the public,” she said.

The Experiments, Successes and Failures

The New Urban Mechanics wields an annual budget of $280,663 and manages the City of Boston’s capital budget innovation fund, which will grow from $1 million to $2 million, for “Work across departments to deploy innovative improvements on streets, online, and in schools using technology and cutting edge design.”

What’s even better is that the budget refers to their work as “experiments,” not civic innovation projects.

It’s fitting because experimenting is what NUM does, from the embryonic idea stage up until a finished product is ready to be deployed and adopted.

Though ideas are formulated differently each time, the results – and the process to get there – often serve as a lesson to the city.

“Sometimes [ideas are] coming internally, or there could be someone we collaborate with in another department,” said Evans. “We have internal entrepreneurs, there are mayoral objectives, we work directly with the community groups, and then there’s the stuff we recognize and kind of kick it around a bit. We come up with a lot of really bad solutions and then hopefully one that’s viable.”

Viability, though, hasn’t been a primary concern for NUM, which boasts a pretty impressive success rate to date.

Only a fraction of NUM products are no longer in use today. As you can see by the data visualization, the education field is where most of the NUM developments have come from to date, followed by both “clicks & bricks” and “participatory urbanism.”

But those represent just completed projects, of which five in total of are no longer used because they’ve been retired or revamped – shown as the lighter hued colors on the graph. Programs still in development or in the pilot stage are not displayed.

We come up with a lot of really bad solutions and then hopefully one that’s viable.

Much of the focus as of late has been in the parking and traffic realm. NUM is piloting a new parking ticket payment system with TicketZen, has tweaked maximum parking hours in the Innovation District to decongest traffic, and helped push through the municipal ordinance to add side guards to city-owned trucks to keep cyclists and pedestrians safe from blind spots.

While several projects, like Oscar or the proposed coffee cart, take up physical space, NUM has worked extensively in the mobile apps realm.

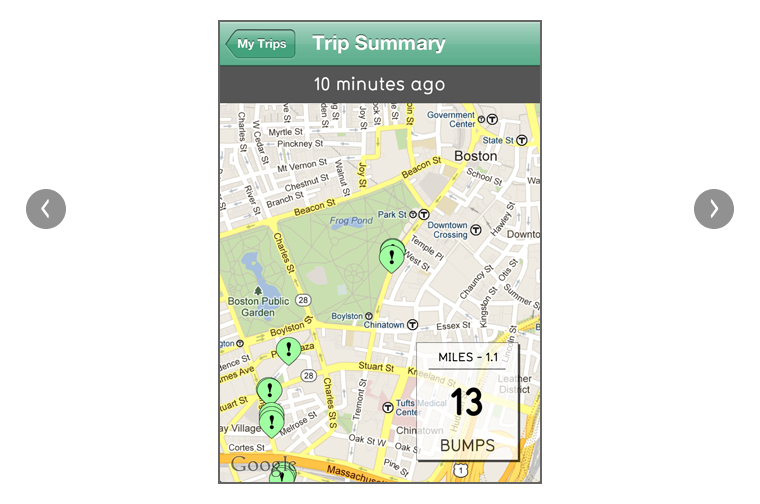

In similar fashion to Citizens Connect, they’ve devised an app called StreetBump that, when activated and a user is driving, tracks the accelerations and decelerations of the vehicle in order to create a data map of potholes and other gaps in our roadways.

It also gathers its data in real-time but unlike with Citizens Connect, users don’t have to stop, snap pictures and write descriptions in order to notify the city of problems in the street.

Both of these apps have gone through a number of versions and will surely be updated as NUM sees fit. But some projects, like those of the artistic variety, have a value that can’t be measured in terms of whether it’s still in use or not.

“Fenway’s 30 Second Cinema” is a temporary installment. Such is the case for “Bird’s Eye Boston” as well, a 3-D model of Boston created with the Boston Redevelopment Authority that offers citizens a different perspective of the city. It also helps to make City Hall’s interior a little more charming. It’s located on the third floor mezzanine where the coffee cart will go.

Still, there are projects that are launched but subsequently retired. Whether it’s an event, competition, app or art project, not everything proves to be successful.

After announcing Requests For Proposals to do something with the 2,200 outdated fire call boxes scattered throughout the city, NUM all but abandoned the idea, saying talks have since stalled. But with the recent release of Wicked Free Wi-Fi, overhauling the boxes is understandably less of a priority.

They’re also piloting a program to crowdsource what Bostonians want to see in vacant street-level storefronts. Announced in April and running through the holidays, this crowdsourcing initiative works by placing four choices in the window for what passersby might want to see occupy the storefront. Those interested in sharing their two cents are then able to text their favorite idea to NUM who will then compile the data and do their best to opt for the most popular option.

What’s Next

The Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics is more than just a group of forward-thinkers set out to make Boston an overall better place to work and play. Each member comprises a municipal body that acts as the glue for all city departments that want to bring innovation to the people.

Sure, NUM has plenty on its own plate in terms of experiments and services, but some of the ideas they take from their constituent departments are invaluable. Though parking might be the civic topic of today, NUM and the Department of Neighborhood Development will fill out a team of internal and external personnel tasked with developing affordable housing with direct access to transit lines. Together, they’re aptly called Boston’s Housing Innovation Lab.

Each new urban mechanic is forthcoming in saying they’re not experts on everything, and fostering relationships with certain City Hall specialists in many cases breathes new life into a design or task.

We spend a lot of time with departments, relationship building, building trust and delivering on whatever’s asked of us.

“This is the key, I think, to our success,” said Jacob. “We don’t work in this sort of waterfall, linear way. We’re constantly learning and testing at all stages of the projects.”

The perpetual tinkering in conjunction with the cross-departmental approach has proven popular for other cities. The launch of the Philadelphia office, with whom they’re constantly in talks, is one example of other cities wanting to emulate what’s done here in Boston.

And others are looking to get in on what’s happening here and in Philly.

Calls are constantly coming in from urban centers across the country and the globe for advice on projects of their own or on how to launch an innovative office like theirs.

“Our interest was in growing the brand and pushing this movement out to other places,” said Jacob of the Philadelphia launch. ” We’ve got a model scaleable to other places that’s based on the approach to the work, not on a particular mayoral edict.”

Perhaps it was Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter who summed up the New Urban Mechanics best when he said, “If they don’t have any failures, they’re not trying hard enough.”

Based on NUM’s portfolio and the near-indecipherable scribblings on seemingly every surface, it seems like they’re trying, failing and succeeding plenty.