In order to make cheaper housing available to middle- and low-income earners, Mayor Marty Walsh’s administration and the Boston Redevelopment Authority are committed to building more units in close proximity to public transit.

The idea is that the city can facilitate dense transit-oriented development, which will provide ample spaces for the workforce at non-luxury housing costs with easy access to the subway, buses or Commuter Rail. This allows for a reduction in commuting costs, such as MBTA passes and gas, so that people can live more comfortably in an urban setting.

At the end of the month the BRA will convene two open house-style meetings to solicit interest and feedback from the public on the beginning stages of its first two transit-oriented housing corridor feasibility studies.

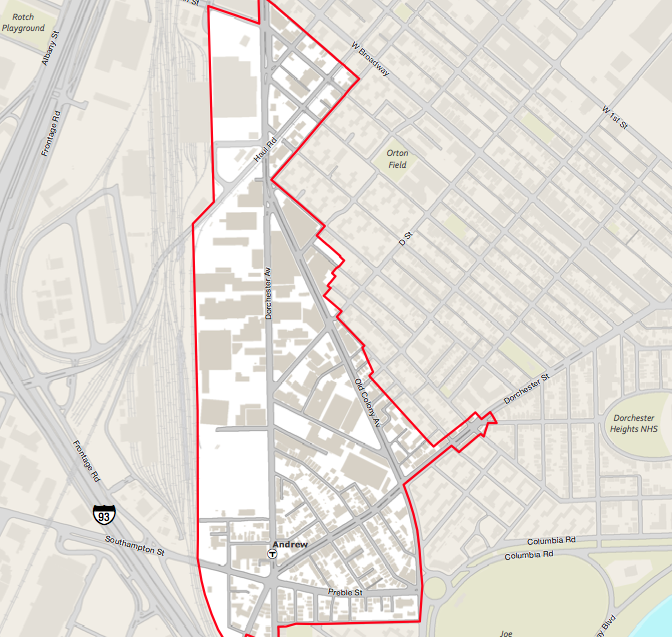

The two corridors are along the Orange Line between Forest Hills and Jackson Square stations in Jamaica Plain in Roxbury, and along the Red Line between Broadway and Andrew stations in South Boston.

According to Mayor Walsh these two particular zones have been eyed with keen interest from developers. The studies will examine such items as zoning codes, public improvements, and best practices for recycling buildings in disrepair for new usage.

The BRA’s determinations will help inform developers on how best to go about pushing their projects through the pipeline, which are increasingly in line with the mayor’s 2030 housing plan for 50,000 new units by the year 2030.

“It’s clear that developers have taken a serious interest in both of these areas, and we should use that as an opportunity to put together a comprehensive vision to guide development in the future,” said Mayor Walsh in a statement. “We have an undeniable need for more affordable housing in the City of Boston. We know these areas have the potential to accommodate new housing, but we want to work with residents to see what else we can do to strengthen their neighborhoods.”

Back in May, Mayor Walsh and a handful of his staffers – including housing chief Sheila Dillon and BRA head Brian Golden – outlined the first quarterly report of the 2030 housing plan.

They also mentioned that between 12 and 15 other transit-oriented sites have been identified as ripe for development potential, barring any issues encountered with its first two studies – it’s important to note, too, that these sites have yet to be finalized.

But the city has already got its hands full with development and construction projects and the BRA is spread pretty thin. At the end of June, the city announced that it reached $1.65 billion in housing starts for calendar year 2015.

If Boston is able to keep up this pace, 138 percent higher than the $692 million in housing starts at this time last year, the city would be riding in the front seat as far as meeting its 2030 goals. And while Boston is clearly in the midst of a housing boom that leaves the BRA shorthanded, it means more jobs for laborers.

“There’s a lot of construction jobs and a lot of people working, so that’s really good news,” Dillon told me. “It also became very clear to us that there has been a shift and developers are developing more affordable [housing] and for the middle-class.”

Some 18 percent of this year’s housing starts are deed-restricted affordable housing, up 25 percent from 2014.

“There really are not a lot of places for middle-income people within the city limits,” Ted Lubitz, Vice President at Related Beal, told me. “Rents in Boston, on the market side, they’ve grown anywhere from 5- to 10- to 15-percent whereas deed-restricted housing doesn’t have that rent growth.”

It seems, though, that the BRA is increasingly unable to keep up with the city’s breakneck development speed. An audit released on Thursday commissioned by the Walsh administration “uncovered several facets of the BRA’s structure and operations that are in dire need of reform.”

Included in that, according to the BRA, is the suggestion that the BRA’s planning division should add staff to support the proactive planning initiatives that are currently underway.

“The city’s being very calculated about how they’re advancing these,” added Lubitz. “Casting a wider net will allow you to take a look at all 15 of those sites and identify which of those will work.”

Lubitz also added that the unique characteristics of each identified site require an original approach to redeveloping them respectively, a notion that somewhat prohibits the BRA from taking on more than two transit-oriented corridor studies, especially given its personnel shortage.

“In the best way possible, we have our hands full at the moment working on Imagine Boston and the Washington Street and Dorchester Avenue planning studies,” Nick Martin, the BRA’s communications director, told me. “We look forward to announcing future planning initiatives as we increase capacity for this work.”

Two open house meetings are scheduled to discuss the Orange and Red Line corridor projects – one on July 28 at 5 p.m. at the Brookside Community Health Center in Jamaica Plain, the other on July 30 at 5 p.m. at the Iron Workers Local 7 Building in South Boston.

Given the emphasis on including the public in this process as well as Mayor Walsh’s call for inventive projects as per the housing plan and the city’s first master plan in 50 years (which goes beyond construction to include transportation, arts and culture, and environmental sustainability), it’ll be interesting to see how the city, BRA and private developers opt to move forward with increased housing around these sites.