Last month, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center announced that conditions for an El Nińo year were developing in the Western Pacific. This month, that picture looks quite different, as meteorologists now say the building El Nińo conditions are likely to fizzle. The impact of that news will likely be felt globally, with California sinking further into despair over a lengthy drought, and India hoping to dodge a dry-weather bullet.

“During El Nińo the water that is normally cold becomes quite warmer — about 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer over the course of a few months,” said Kerry Emanuel, professor of atmospheric science at MIT . “The seasonal downpours that are usually in the tropical portions of the West Pacific shift quite far to the east, to places that are normally very dry.”

In California, El Nińo would help–but not without risk, Emanuel said.

“If we have an El Nińo it can up the chances for heavier rain (in California) this winter. There is the problem, of course, that you can go from famine to feast in southern California and end up with terrible mudslides. But on the whole we hope that we will have a rainy winter,” Emanuel said.

In July, signs of El Nińo were beginning to show, as India entered its worst state of drought since 2009 – another El Nińo year. According to Skymet Weather Services, an India-based weather forecast service, El Nińo has been the largest factor leading to India’s lack of rain. Now, however, the building El Nińo momentum has slowed, with the San Jose Mercury News reporting meteorologists predicting a weak El Nińo to none at all.

Californians are watching those reports carefully. The Golden State has been having its worst drought since the late 1800s, a three-year dry spell. According to the L.A. Times, southern California realistically only has enough water to push the state through another 12 to 18 months of dry weather.

“El Nińo typically raises the global average temperature by quite a bit. We haven’t had a spike in quite a while….The ocean’s heat content has increased.”

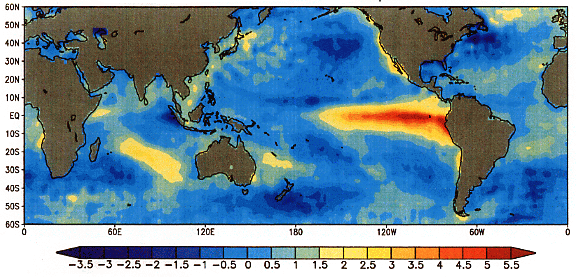

The El Nińo weather system, officially El Nińo Southern Oscillation (ENSO), is somewhat cyclical. Conditions arise every four to seven years, warming of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean due to wind changes. When easterly trade winds relax, pools of warm water accumulate in the western tropical Pacific and are allowed to move east, increasing the overall surface temperature of ocean waters across the equatorial Pacific. These stretches of overly warm water can impact weather worldwide for up to two years.

El Nińo doesn’t have much impact in the Northeast–Emanuel said it’s “almost irrelevant” in New England–but increased water temperatures do impact global warming. According to Emanuel, because of the increase in ocean temperatures across the Pacific, El Nińo significantly raises the average atmospheric temperature.

“El Nińo typically raises the global average temperature by quite a bit. We haven’t had a spike in quite a while – since the major El Nińo event in 1998. The ocean’s heat content has increased (since then).”

Californians are still holding out hope for rain, but chances are slimmer than they were a few weeks ago. Dwindling El Nińo conditions are not good news, “especially if we are using El Nińo as an optimism index,” Golden Gate Weather Services meteorologist Jan Null told the San Jose Mercury News. “It’s like in poker,” he said. “If you have one fewer spade out there, the odds of getting that flush are less.”

However, El Nińo might not be such a big deal for Californians either way. According to a study released in July by the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, El Nińo most likely wouldn’t pull California out of its drought. “Statistically,” the study reads, “2015 will be another dry year in California – regardless of El Nińo conditions.”

“California’s agricultural economy overall is doing remarkably well…but we expect substantial local and regional economic and employment impacts,” said Jay Lund, co-author of the study and director of the university’s Center for Watershed Sciences, in a press conference in D.C. last month.

The university’s study shows that this year’s drought has cost $1.5 billion to California agriculture, caused the termination of over 17,000 seasonal and part-time agriculture jobs. The statewide cost of the drought this year is $2.2 billion.

While California is taking a hit economically due to lack of rain, the cost of classic Cali crops like nuts, dairy and wine grapes are likely to go unaffected as these prices are driven more by market demand than anything the weather might cause, the authors of the study said.